Published

9th October 2024

Categories

The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The End of Eras

With great sadness, we pass from the second Elizabethan age. Our Queen was a constant during this period of intensely rapid change. Across the political spectrum, we can acknowledge her ceaseless responsibility to her people. She retained her dignity as monarch throughout her reign, supported by her faith and her humanity, which was obvious to all.

Despite her failing health, her last official act, last Tuesday, was to invite Liz Truss to form a government—the 15th Prime Minister during her reign. The official pictures show the Queen undertaking the task with a warm smile and a welcoming handshake. The Prime Ministers are perhaps more signals of change than constancy. Truss has moved commendably quickly to propose action on the energy crisis.

Underneath the action is a stronger sense of political principle than under Johnson, May, or even Cameron. In this respect, Truss seems to want to emulate Margaret Thatcher by being a strong support for business. Within the energy policy proposals, a six-month energy price cap for businesses will be welcomed by many. We look at the emerging energy policies in the UK and Europe in the article below.

The finance-related cabinet team is also imbued with a radical pro-business, deregulatory agenda. Kwasi Kwarteng is said to be focused on policies that create an attractive UK environment for global firms. The current refusal to consider windfall taxes is such a signal, as is the proposal made during the Conservative leadership campaign to cut corporate taxes. The appointment of John Redwood also signals a wish to return to the reforming years of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership.

The immediacy of Truss’s proposals is commendable, but it is also clear that the political need for speed has led to only partially formed policies. The Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Resolution Foundation both point out that it is remarkable for such huge proposals to be costed only in the most sketchy way—the announcements told us about achieving outcomes without any real clarity on how they will be achieved.

This is not to say that the policies will be ill-formed. The aims are laudable, but we just don’t know yet whether they will be achieved in a way that solves problems or adds to them. One aspect of this is the growing dissonance between fiscal and monetary policy.

Both Bloomberg and JP Morgan Research expect that the Bank of England will still raise rates, although the energy price caps have the effect of lowering consumer price inflation forecasts over the next year, hopefully going some way toward lowering future inflation expectations. Both expect that the fiscal boost will support the economy enough to avoid more than one quarter of negative growth next year. This means that both expect rates to peak at a higher level than before. However, neither expect rates to go higher than 4%.

The interest rate market was already discounting rates above 4% before they published their research. The biggest conundrum will be around the new debt that will have to be issued by His Majesty’s Treasury. During the pandemic, the Bank of England bought much of the debt issued. It will be difficult to consider a repeat of that while inflation and a weak sterling are its monetary problems. Over the past two weeks, gilt yields have risen, and the value of Sterling has fallen. Potentially, they could go further if the details of the policies show open-ended costs.

During her campaign, Truss talked of reestablishing a money supply-led monetary policy, in the manner of the early Thatcher years. However, her fiscal largesse is some way from the economic policies that Thatcher favoured. The era of neo-classical economics may be also passing.

Coping with the energy crisis

The post-pandemic inflation boom has taken many turns over the past couple of years. It started with surprisingly diverse supply-chain problems, increasing prices for raw materials. Growth, fiscal overhang, and Covid then caused labor markets to tighten dramatically – pushing central banks into the aggressive policies we have seen this year. Fading growth and business confidence (outside of the US, at least) have recently lessened concerns of a wage-price spiral, but the war in Ukraine has kept inflation pressures excruciatingly high.

Now, the threat of price rises comes mostly from the cost of energy. This is caused by a severe cost-push around natural gas and electricity – and it is overwhelmingly focused on Europe. As we have written before, the British and European economies face serious problems around energy supplies. With a harsh winter looming and no sign of loosening supply, blackouts and gas rationing are expected in Germany and some of its neighbors. Where rationing is not taking place, costs are skyrocketing for consumers and – especially – businesses.

The policy response to this crisis is crucial. Just as at the start of the pandemic, inaction would likely precede widespread bankruptcies, closing businesses, and a subsequent spike in unemployment. Clearly, support is needed, but the details are tricky. If government aid simply translates into an increase in the aggregate demand for energy, the world’s undersupply will grow, and inflation will only get worse.

Finding that balance has led to various plans from politicians. Germany delivered a temporary big cut to its tax on diesel and petrol and has set out various support schemes for households, with utility companies able to apply for state support. A broader corporate support package is still in the making and will probably deploy unused funds from Covid packages.

New British Prime Minister Liz Truss announced last week a general price cap on household energy bills at £2500 for a typical household. Such a drastic measure certainly lowers energy prices as experienced by consumers in the short-term, and thereby reduces CPI inflation readings that central banks usually target (as seen in Germany’s recent CPI numbers). The problem, though, is that these do little to address the underlying supply-demand imbalance. Without higher energy prices, there is no incentive to reduce consumption – meaning price pressures remain. From announcements last week, it also appears UK companies will benefit from a price cap lasting six months.

Taking a different approach, the EU is reportedly planning to change the way the electricity market functions to avoid sudden price rises. The aim is to decouple end energy prices from wholesale gas prices, thereby softening the blow of any sudden supply-side shifts. There are also proposals to redistribute energy companies’ excess profits.

Similarly, representatives from G7 nations announced last week that they will seek to impose a price cap on Russian oil. Finance ministers from the US, UK, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and Canada will now pressure importers to keep oil prices below a set level – starting in December for crude and then February 2023 for refined products. The idea is that insurance and financing will be denied to any ships carrying Russian oil above the agreed price cap. While this has primarily been presented as a geopolitical play to hurt Moscow’s finances, it could also have a critical impact on prices down the line. Plans like these are a positive sign because they act higher up the supply chain, meaning that businesses as well as consumers face lower inflation pressures. Unfortunately, this measure applies only to oil which, as mentioned, is not the key driver of Europe’s price pressures. No similar plans exist for gas supplies, although something along those lines had been floated on a European level, too.

The problematic aspect is that price caps take out the clearing mechanism a price set by the market forces is supposed to achieve. In many countries, spending plans or price caps are being financed by (or coming at the expense of) energy company profits. Previous Chancellor Rishi Sunak already announced a “windfall tax” on energy companies over the summer, and there is renewed political pressure on Truss to do so again with regard to her new fiscal support. However, it appears the current support package will be fully debt financed.

Regardless of the political motivations, debt-financing is a risky move in the current economic environment. Whatever way you slice it, the problem is simply an acute undersupply. Supporting the worst-off by redistributing wealth at least takes money from elsewhere – thereby (theoretically) keeping aggregate demand neutral. Debt-financing instead keeps real prices high and creates inflationary pressures further down the line. This attitude is likely to put pressure on the Bank of England (BoE) to tighten monetary policy further or should in theory. This on the assumption that hopefully pressure on the BoE to finance the current spending plans will stay contained.

This would mean that we are in a rather “classical” situation where a higher fiscal deficit actually puts upward pressure on yields. After years of fiscal austerity, coupled with low inflation readings and hence supportive monetary policy, this is a different framework to operate in. So tighter monetary policy will push borrowing rates up and weigh on businesses and households alike. The benefit to that plan, though, is that fiscal transfers can at least be more targeted than monetary policy. In the best-case scenario, this creates a real (inflation-adjusted) wealth redistribution by stealth. In the very worst case, it damages the whole economy and creates unemployment.

The Pound has already fallen to its lowest dollar value in decades, and further debt or inflation pressures could weigh on it further. In this context, it will be vital for the BoE to keep its independence from politics. From a more general political point of view, the UK and the EU are at the cusp of defining Europe’s (energy) future – will the continent be able to invest sufficiently in its energy infrastructure, such that supply disruptions are less likely to hit?

House price strength fades

The current inflation spike has hit virtually all parts of the world economy, and property is no exception. According to a report from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), global house prices jumped a whopping 11.2% from April 2021 to March 2022. This was the first double-digit jump in property prices since the global financial crisis of 2008, and the rise was broad-based, affecting both emerging and developed economies.

This was good news for current homeowners, but it points to a real stretch of affordability across multiple markets. Indeed, rapid house price gains have been a big direct and indirect contributor to the cost-of-living crisis facing the developed world. Even adjusting for inflation, global residential property prices grew 4.6% over the twelve months to the end of March 2022. That is on a CPI basis, which BIS uses to calculate real (inflation-adjusted) price gains, but the jump most likely feels starker for buyers and renters. If we deflate the nominal figure by wage gains rather than CPI, we estimate that the surge is around 7%.

In terms of future demand, affordability is the key thing to watch, and on that basis, the wage-adjusted figure is revealing. While homeowners’ balance sheets are flattered by the asset price rise, unless the gain is monetized, consumers end up being squeezed for housing – and the 4.6% real figure is significant. Bear in mind that, at the start of this year, inflation was already running red-hot around the world. For property prices to post a gain comfortably above inflation indicates how strong the market was – and suggests that house prices were themselves a big contributor to global inflation.

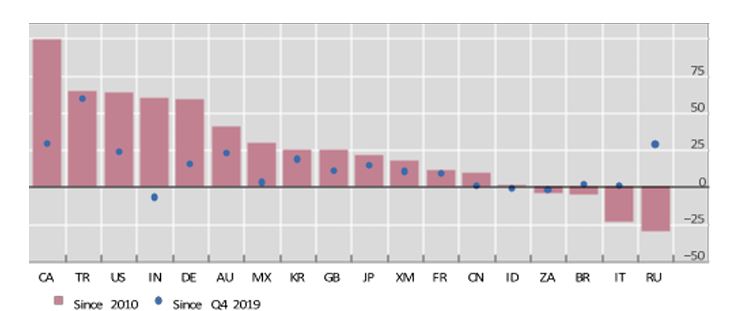

While most regions joined in the price surge, gains were not equally spread. Emerging markets (EMs) posted a 1.6% year-on-year gain in real terms, while developed markets recorded a massive 8.5% aggregate jump. The 12% real terms gain in the US was impressive enough, but it was outshone by increases of 14% and 20% in Australia and Canada, respectively. Turkey, which has been plagued by currency woes for years, saw an incredible 35% gain in its housing market.

Housing markets were much more subdued outside of major Western nations, though. Middle Eastern and African residential property climbed just 2.7% in the first quarter of 2022. Meanwhile, Asia and Latin America actually recorded falls of 1.3% and 1.5%, respectively. While property prices are certainly a big part of this year’s inflation story, they were on an uptrend long before the current supply-side shocks.

BIS looked back at the twelve years since the Great Financial Crisis, deemed to be 2010. They calculate that real house prices are 29% above where they were after the global financial crisis, and the gains are again unevenly shared: EM residential property has gained 19%, while developed markets have jumped 41% over the same period. From a longer-term perspective, this is quite astonishing. As many in the UK know, housing now accounts for a significantly bigger chunk of people’s expenses than it did in 2008.

Canada’s house prices have doubled in real terms since 2010, while 60% rises have been recorded in the US, India, Germany, and the US. But like many other global economic trends, house price growth has accelerated since the start of the pandemic. Compared to the last quarter of 2019, residential property has jumped by over 20% in the US and Australia, and by 30% in Canada.

India is the big post-pandemic negative outlier, while Russia was actually one of the best performers over that time.

Taking a longer-term view, we can clearly see that some regions have not shared the growth of the last ten years. Italian residential property is significantly cheaper than it was in 2010, with only a slight bump up since the start of the pandemic. This is likely down to the deep malaise in the Italian economy, and specifically its banks’ longstanding problems with non-performing loans.

What does this mean currently, and for the future of the housing market? Clearly, affordability can only stretch so far before it heads back to a more normal level. Developed economies have pushed this limit over the last decade by keeping interest rates at historic lows and pumping markets full of liquidity. Buyers thereby had great access to financing, even if their wages could not keep up.

Now, though, the financing environment is entirely different. Central banks have tightened policy significantly to combat runaway inflation and are signaling higher rates ahead. Add to this a severe cost-of-living squeeze and falling real disposable incomes, and it is hard to see how demand could keep up with soaring prices. This is not to say a crash is coming – but a slowdown or slight reversal seems inevitable.

Sure enough, more recent signs back this up. After climbing high into the first three months of the year, Australian house prices seem to have turned downwards, even before adjusting for inflation. The same is true in Germany, which had before been experiencing its strongest property market since the 1970s. In the UK, prices are still increasing, but the gains are small and below consumer price inflation. The Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors’ monthly report (published Thursday 8th September) showed a decline in the house price expectation balance to 53, consistent with expectations of a slowing but not negative market. Crucially though, Britain’s housing market no longer looks like a source of overall inflationary pressure.

China – now a key region in the global property market – has been weak for some time, unlike other major economies. The slow-motion collapse of property developer Evergrande has had severe knock-on effects for the country’s house prices. While these no longer look like signs of extreme stress, it will be hard to find a significant upside.

We’d note that the Chinese have also had impacts on other nations’ property markets, especially in the cities among new-build apartments. It will be interesting to see whether, in the medium-term, their liking for property assets abroad has been dented by a loss of faith in the domestic market.

The main exception to the recent global price stagnation is in North America, where house prices are still rising at or above inflation. During the pandemic and up to this April, the US and Canada saw new-build costs rise sharply, with lumber prices quadrupling. Now mortgage costs have hit 10-year highs, removing a lot of the surge in demand, and lumber prices are back at pre-pandemic levels. That helps to reduce some of the upward price pressure, but the strong labor market continues to give the housing market a strong underpinning.

Both the timing of this reversal and the comparatively better fortunes of the US should be expected. Russia’s war on Ukraine led to a major shakeup in global energy prices but hit Europe by far the hardest. Cost pressures are much more pronounced in Europe than across the Atlantic, and consumers are therefore much more constrained. US energy costs have been much milder, and its consumers have fared better. How much longer that can continue remains to be seen – particularly with the Fed tightening policy. But with winter approaching, we should not expect the outperformance to end in the short-term.

If you would like to download this material, or prefer it in another format, it is also available as a PDF. You can access the PDF version here.

This material has been written on behalf of Cambridge Investments Ltd and is for information purposes only and must not be considered as financial advice. We always recommend that you seek financial advice before making any financial decisions. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested. Please note: All calls to and from our landlines and mobiles are recorded to meet regulatory requirements.